Soft Floors in Auctions, Zeithammer, Management Science, 2019

We continue exploring research on recent trends in online auctions this week. In a highly industry relevant paper, Robert Zeithammer studies the revenue properties of soft floor prices in auctions. The idea of soft floor prices gained popularity around the year 2013, when various ad exchanged introduced them. While some exchanges deprecated soft floor pricing after a rather short period of time, they are still in widespread use.

Zeithammer’s paper is the first theoretical treatment of soft floors as applied in the RTB industry. His main conclusion is:

the use of soft floors is misguided because they complicate bidding

and have no effect on expected revenue.

A first price auction – sometimes

What are soft floors? Suppose an auctioneer has a single object for sale, such as an impression. She sets a hard floor price h and and a soft floor price s for the auction. The auction then collects bids and orders them from high to low. Allocations and pricing are then as follows:

- If the highest bid is above s, the highest bidder wins and pays either the second highest bid or s, depending on what is higher

- If the highest bid is below s but above h, the highest bidder again wins but now pays her bid

- If the highest bid is below h, the auctioneer keeps the object.

The first case is essential a second price auction with the soft floor as reserve price, the second case is a first price auction and the value of the highest bid determines which auction we are in.

The motivation for introducing soft floors is generally to increase the revenue of the auctioneer. A post by mopub states “The goal is to ‘harvest’ higher bids while not compromising on lower bid opportunities.”

When can we expect higher revenue?

One perspective might be that first price auctions achieve higher revenue than second price auctions because they simple charge higher prices for the same bids. Hence, soft floor prices, by sometimes charging first prices, might also increase revenue. However, since Myerson (1981) we know that under commonly made assumptions, including symmetric value distributions of bidders, any mechanism that results in the same allocation must also have the same expected revenue. This is the celebrated revenue equivalence theorem. The practical implication of the result is there is no way to optimise expected revenue other than changing the allocation. Reserve prices, which are generally effective in optimising revenue, achieve this by sometimes not allocating the item to any bidder.

Maskin and Riley (2000) relaxed the symmetry assumption on bidders’ value distribution and showed that the revenue equivalence theorem does not hold in this case. The revenue predictions depend on the auction type and the value distributions.

Expected revenue with soft floors

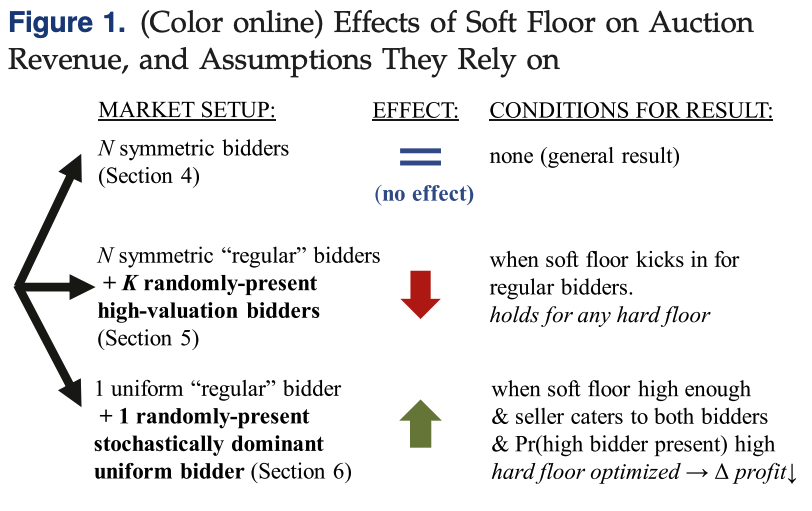

As the above results suggest, any study of expected revenue requires some model of the demand side, which is generally done by defining bidders’ value distributions. One of the main results of the paper is that revenue equivalence indeed holds for auctions with soft floors under the standard symmetry assumptions. Zeithammer then studies other settings with asymmetric distributions, in the spirit of Maskin and Riley. In those settings, revenue with soft floors can be lower or higher. The below figure summarises the main conclusions regarding auction revenue depending on different models of the demand side.

Identical expected revenue with symmetric bidders

The paper contains a proof that bidding strategies are still monotonic in the independent private values model with soft floors, where all bidders have private information independently drawn from the same distribution. This then means soft floors have no impact at all on the allocation, and hence Myerson’s result applies. This is true even when auction participation is random and the soft floor is not known to bidders.

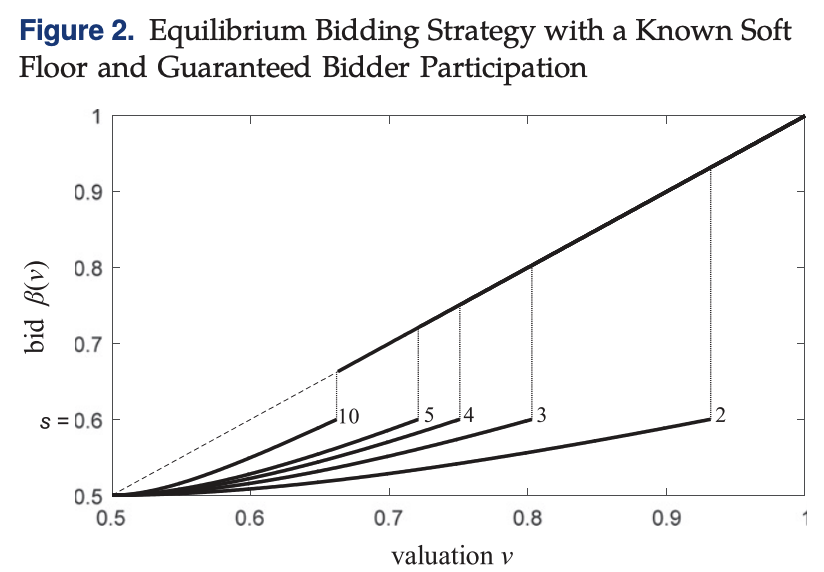

Figure 2 shows there is a kink in the equilibrium bidding strategy. Essentially, bidders with values above some threshold behave like in a second price auction and bid their valuation. However, bidders below the threshold shade their bids, like in a first price auction. The threshold depends on the number of participating bidders.

Randomly appearing high valuation bidders

A common motivation for soft floors in the industry is the occasional entry of high valuation bidders to the auction, which retargeting being a common use case.

If such a high-value advertiser were always present, there would be little benefit to soft floors—the seller could simply increase the hard floor; but such a high-value advertiser may not participate in every RTB auction, so a soft floor might seem to be a clever adaptive mechanism that automatically activates a higher reserve price only when the

advertiser does appear (Weatherman 2013). In contrast to this industry intuition, I show that adding randomly appearing asymmetrically high bidders always makes low-enough soft floors suboptimal for the auctioneer.

The law of unintended consequences may apply here. Zeithammer shows that when high value bidders are guaranteed to have valuations above regular bidders, soft floors low enough so that high bidders all face second pricing actually decrease revenue, as the strategic bid shading by regular bidders offsets the additional price pressure on high bidders.

The last word

Soft floors have emerged in the RTB digital display advertising industry as a potential tool for increasing publisher revenues. This paper shows soft floors are not likely to deliver on this promise in the long run when the bidders are ex ante symmetric, even if the auctioneer keeps the exact soft-floor level hidden from the bidders, or when bidders participate in the auction randomly. Adding randomly appearing “high” bidders (e.g., retargeting advertisers in the RTB context) to the auction does not automatically make soft floors profitable either: the profitability of soft floors depends on their magnitude and on the amount of valuation overlap between regular and high bidders. To illustrate the nuanced profitability of soft floors in RTB-relevant asymmetric markets, this paper provides both an example in which soft floors reduce revenue and an example in which they increase it.