This week’s paper is about online learning methods to measure the difference in utility between bidding truthfully and following the optimal bidding strategy when the auction mechanism does not satisfy incentive compatibility (IC) and is a black box to bidders. It is relevant for advertisers and demand side platforms (DSPs), as high utility differences and large market volumes will lead to positive returns of investment in bid optimisation systems.

On the one hand, in Game Theory and Mechanism Design, most of the existing literature focusses on maximizing revenue for the auctioneer without knowing a priori the valuations of the bidders, as well as optimizing the bidding strategy from the bidder side. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper on testing IC through online learning approach.

Practical challenges with violations of incentive compatibility

The source of the underlying challenge is a potential lack of IC in the advertising ecosystem. If IC is satisfied, the bidding problem is simple, as bidding the advertiser’s valuation will maximise her utility and the only problem of the advertiser is to assess her valuation. If the auctioneers optimisation problem can be solved exactly, the VCG mechanism is IC. While auction theory has influenced the design of online auctions, not all auctions we see in practice are IC and the quality of the auction designs differ. For example, some publishers apply “dynamic reserve prices” or “soft floor prices” that both violate IC. A lack of IC is challenging for both advertisers and DSPs, as they have to invest in figuring out optimal bidding and pacing strategies that generally differ by platform and publisher.

Since (the lack of) incentive compatibility impacts bidding strategies for advertisers and the quality of the product that a DSP offers, it’s important to understand the end-to-end incentive compatibility of an ad system.

Assessing the severity of IC violations

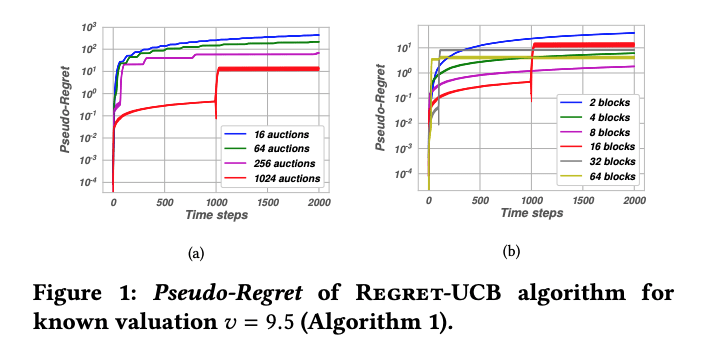

While IC is a binary property, non-IC auctions may differ in some sense on how severe the incentive problem is. For example, a first price auctions is in some sense worse than a second price auction with a “dynamic reserve price” of 50 % of the highest bid. To quantify this notion, the authors introduce the notion of IC-regret:

IC-regret is the maximum expected difference in utility between selecting the optimal bid b_i and bidding valuation v_i given bids of other bidders b_(-i). IC-regret is zero for IC-mechanisms.

Given black-box access to the auction mechanism, our goal is to 1) compute an estimate for IC regret in an auction, 2) provide a measure of certainty around the estimate of IC regret, and 3) minimise the time it takes to arrive at an accurate estimate.

Black-box access means the advertisers only observe allocations and payments after submitting bids. This reflects many real world scenarios where either a detailed description of the mechanism is not available to bidders or this description can not be trusted.

Learning IC regret online

The authors solve the learning problem using tools from the combinatorial bandit literature. Basically, the bids are the actions taken by the bandit and the observed utility is the outcome. The algorithm – called the test bidder in this case – dynamically selects bids to optimise an objective. They provide error bounds for determining the IC regret as a function of time. The problem is approached from two practical perspectives:

- Advertiser Problem: The advertiser knows his valuation and thus only selects bids to determine IC regret.

- DSP Problem: The DSP does not know the valuation of advertisers and it wants to ensure the regret is low for all participating advertisers. Thus, it is interested in the regret for the worst-case valuation. It hence selects bids AND valuations to determine regret.

The learning task of the test bidder is to generate a sequence of bids (Advertiser problem)/sequence of bids and valuations (DSP problem) to minimise the pseudo-regret, defined as the difference of the time-cumulated optimal IC regret and the time-cumulated empirical regret for a given time horizon, valuations and bids.

The learning task is solved using a Regret-UCB-algorithm that performs the following steps in the advertiser problem:

- Compute upper confidence bound (UCB) on the expected utility for each bid

- Choose a fixed number of bids associated with the highest UCB from step 1

- Submit those bids to the auction, along with a bid equal to the valuation

- Observe allocation probabilities and payment distributions, update estimates and go to step 1.

The final section of the paper validates the theoretical convergence results of the paper in simulations with a Generalised Second Price (GSP) auctions, which is known to not be IC.

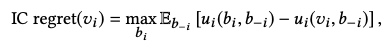

The first figure shows how the pseudo-regret converges over time for different numbers of auctions and blocks for known valuation. Blocks correspond to the number of different bids submitted per time period to the available auctions.

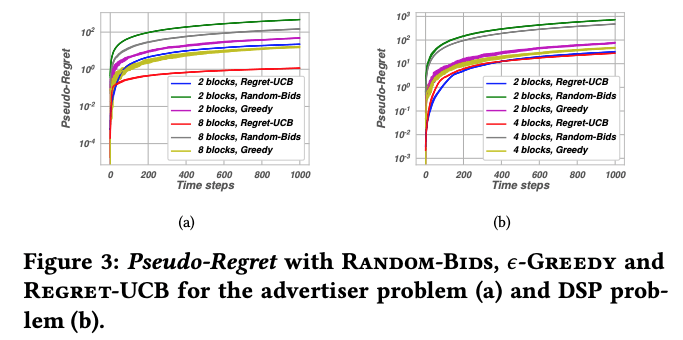

Figure 3 shows the Regret-UCB is generally superior to random bids and epsilon-greedy for different block selections in both the advertiser and the DSP problem.

Closing thoughts

Given the massive amount of value exchanged in online auction markets, the lack of transparency of many auction systems and the revival of the first price auction in some markets, the methods described in this paper can be of high value for any advertiser or DSP interested in the properties of the markets they are operating, as understanding those properties will help guide bid optimisation methods and investments and ultimately drive ROI.